I took an early retirement and moved away from Oregon when my husband, Gary, died. Because housing is expensive in this destination resort area. Because my monthly income was significantly reduced. Because Son Jeremy and DIL Denise offered free rent in southern California.

I’m back in central Oregon to take care of some pinched nerve pain only to discover that this place with its incredible people and so many fabulous memories feels like home.

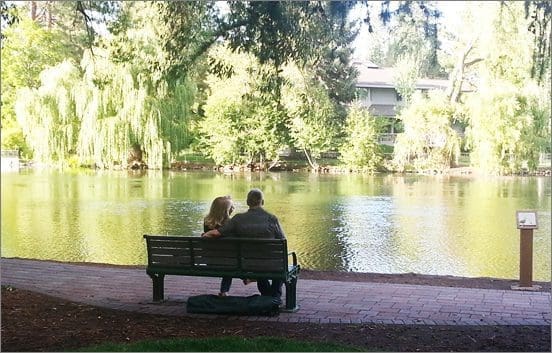

Bend, Oregon – August 2014

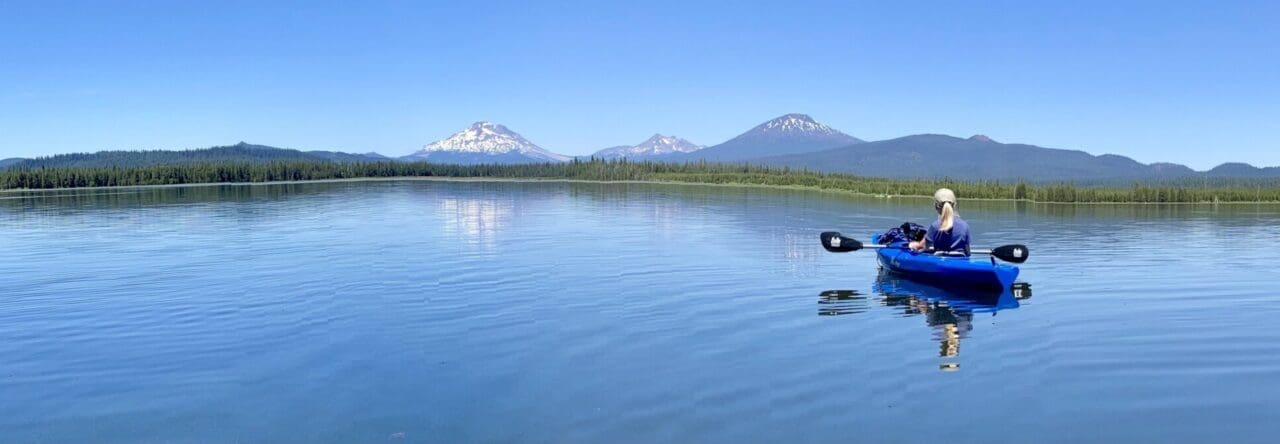

Bend, Oregon – August 2015

There has been this pesky concern filtering through my brain. Why is it not difficult to return to this place where Gary died? Why have I not cried myself to sleep these past eight months? Why this peace? If I’m not grieving correctly now, will it all dump on me unexpectedly?

I captured a few responses to my concerns:

Everyone processes grief in his/her own way. Which means there is absolutely nothing wrong with not crying myself to sleep at night. Not being more sorrowful now doesn’t necessarily mean I’ll fall into a deep pit of depression later.

Gary and I had the gift of time. We had ten years of receiving bad news, sorting through it, and then moving forward with life. While we don’t want to bury our heads in the sand, it is possible to keep our thoughts optimistic and realistic at the same time.

I am blessed with an amazing support team. Kids and kids-in-law. Siblings and siblings-in-law. Friends. People from our cancer community. Co-workers at the cancer center. People who know how to do cancer. Incredibly loving, get-me-through-being-alone people. Investment in community pays high dividends.

Hubby and I had/have strong faith. When we experience hard things, there is a tendency to question: Why me, God? Why would you allow this? But how often do we ask Why me? when we’re bombarded with the blessings of life. Breath. People to love. People who love us. The beauty of a water color sunset. Music and the ability to hear it. Work. A roof over our heads. The freedom to travel. Laughter. Hope. We’re good at complaining. When shouldn’t we be good at counting blessings?

And then, out of curiosity, I did a little reading and discovered that I had been adhering to two fallacies about grieving that have not stood the test of science. According to an article by Hal Arkowitz and Scott Lilienfeld, psychology professors, “Two Big Myths About Grief,” the two common misconceptions are these:

• The bereaved inevitably experience intense symptoms of distress and depression.

• Unless the griever ‘works through’ their feelings about the loss, they will experience delayed grief reactions.

“Neither belief holds up well to scientific scrutiny,” write Arkowitz and Lilienfeld. “Reactions to a loss may depend on a person’s relationship to the deceased … as well as whether the death was sudden, violent or drawn out. We can confidently say that just as people live their lives in vastly different ways, they cope with the death of others in disparate ways, too.”

In a December 2013 piece, “The Secret Life of Grief,” Derek Thompson comments on Elisabeth Kubler-Ross’s five stages of loss. “Kubler-Ross, a Swiss-born psychiatrist, interviewed patients at a Chicago hospital about the experience of dying. She devised a theory of five periods, from anger to acceptance, with each stage serving an essential part in the mourning process. Her book, On Death and Dying, [written in 1969] became a national bestseller, but it … was shoddy science based on people who were dying, not people who were grieving.”

Thompson visited George Bonanno whose work has redefined the science of grief research. “By studying grief like any other psychological condition,” writes Thompson, “Bonanno has exposed the history of bereavement research to be a thread of fables: ‘One of the stickiest myths about loss is that it requires extensive processing.’ … To the contrary, Bonanno has found that those who seem to be working hardest with their grief often report the hardest coping. ‘The more people engaged in their most intense emotions, the longer they would be grieving,’ [Bonanno] said.”

Apparently 50-60 per cent of us appear to be fine after loss. “Scientists used to consider these patients tragic actors, shoving their feelings into the core of their bodies, where they would only explode with volcanic violence in dreadful ways later in life. But this, Bonanno says, might be the biggest myth of all.”

So, is it possible to have joy in the middle of hard things? And peace? Yes and yes.

By riding the wave of grief rather than trying to stand up against it, by immersing myself in community, and by leaning in close to God, I have experienced unexplainable peace.

This from Philippines 4:6-7 —

Do not be anxious about anything, but in everything by prayer and supplication with thanksgiving let your requests be made known to God. And the peace of God, which surpasses all understanding, will guard your hearts and your minds in Christ Jesus (ESV).

P.S. If you have found this post helpful, please share, tweet or pin!

Leave a Reply